Katerina Gordeeva: In memory of Ekaterina Genieva. “It’s not scary to die. It’s scary to answer questions

On July 9, 2015, at the age of 70, the famous cultural and public figure, General Director of the All-Russian State Library for Foreign Literature named after M.I. Rudomino Ekaterina Yurievna Genieva (04/01/1946 - 07/09/2015).

On July 9, 2015, at the age of 70, the famous cultural and public figure, General Director of the All-Russian State Library for Foreign Literature named after M.I. Rudomino Ekaterina Yurievna Genieva.

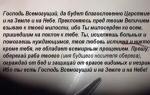

…Sooner or later we will all cross over there to be reunited in the heaven promised to each of us by the Lord Jesus Christ.

And this transition will be bright and joyful for us if we lead a worthy and righteous life, which Ekaterina Yuryevna led

Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk at the funeral service for E.Yu. Genieva

E.Yu. Genieva was born on April 1, 1946 in Moscow in the family of actor Yuri Aronovich Rosenblit (1911-2002) and surgeon Elena Nikolaevna Genieva (1917-1982). Previously, Ekaterina spent her childhood in the family of her mother’s parents: hydrological engineer Nikolai Nikolaevich Geniev (1882-1953) and Elena Vasilievna (née Kirsanova; 1891-1979). My grandmother came from a noble family and spoke 14 European languages. She was a member of select literary circles, and in the summer of 1921-1926 she stayed with the poet and artist Maximilian Voloshin, in his House of the Poet - a free holiday home for the creative intelligentsia in Koktebel (Crimea).

Elena Vasilievna, a deeply religious woman, gave her granddaughter her first knowledge of Christianity. During the summer months they lived in a dacha at the “43 km” station on the Yaroslavl road. E.Yu. Genieva recalled: “Every morning my grandmother and I sat on the sofa, she opened huge volumes of the Bible with illustrations by Gustave Doré and explained in good French what was drawn in the book.” Often they, together with their neighbors, undertook a pilgrimage to the Trinity-Sergius Lavra. Elena Vasilievna was friendly with the abbot of the monastery of St. Sergius, Archimandrite Pimen (Izvekov); the future His Holiness Patriarch visited her at 43 km. Young Katya loved to play hide and seek with her father Pimen: the girl hid in a priest’s cassock, and he pretended to be looking for her.

Perhaps, Ekaterina Yuryevna’s most vivid “church” childhood memories were associated with the appearances at the dacha of “handsome bearded men who instantly changed their clothes and became exactly like those priests whom I saw when I went to services in the Lavra.” These were clergy of the Catacomb Church - a group of clergy and laity of the Russian Orthodox Church, which in the 1920s did not accept the course of the Deputy Patriarchal Locum Tenens Metropolitan Sergius (Stragorodsky) of rapprochement with the Soviet government and was in an illegal position. Elena Vasilievna belonged to the “catacombs” and provided her home for secret Divine liturgies.

In the first half of the 50s, a frequent guest at the Genievs’ dacha was a young parishioner of the Catacomb Church, Alexander Men, whom his relatives and friends called Alik. Elena Vasilievna was friends with his mother, Elena Semyonovna. The future famous shepherd and theologian spent a long time in the miraculously preserved noble library, which contained many volumes on religious topics, and worked on his main book, “The Son of Man.” Katya was offended by the black-haired young man who refused to play with her, being absorbed in reading.

In 1963, 17-year-old Ekaterina entered the Romance-Germanic department of the Faculty of Philology of Moscow State University and, in her fourth year, seriously took up the works of the Irish writer James Joyce. In 1968 she defended her thesis on the works of Joyce, and in 1972 - her PhD thesis. Already in Ekaterina Yuryevna’s student scientific studies, qualities were evident that were noted by everyone who knew her - integrity and willpower. The author of Ulysses and Dubliners was considered an ideologically alien writer in the USSR; translations of his books were subject to censorship, and in the Stalin era they were completely banned. “Senior comrades” from Moscow State University persuaded Genieva to take a less challenging topic, and her dissertation was sent for redefense to the Higher Attestation Commission. But the obstacles did not bother Catherine at all.

In addition to the “arrogance of a young researcher who was convinced that he could cope with the complex text of this modernist writer,” Genieva’s attention to Joyce was fueled by family history. Once Katya accidentally overheard a conversation between her grandmother and her housekeeper and close friend E.V. Verzhblovskaya (they talked in a whisper and in English), in which a strange phrase was heard: “He was arrested because of joy.” Only years later, Katya realized that she mistook the name of the Irish classic for the word joy (“joy”), and it was about the wife of Verzhblovskaya I.K. Romanovich, a promising translator who worked on the novel “Ulysses” in the mid-30s. He died in a camp near Rybinsk in 1943, after serving six years. His widow will take monastic vows with the name Dositheus, and later become a typist for Father Alexander Men.

After receiving the academic degree of Candidate of Philological Sciences, the search for work began. “As soon as the personnel officer of the Institute of Foreign Languages or APN glanced at the questionnaire, where my half-Russian and half-Jewish origin was indicated, and made inquiries about the topic of the dissertation, ... all bets immediately disappeared somewhere,” wrote Ekaterina Yuryevna. Only the All-Union State Library of Foreign Literature opened its doors to her. At first, Genieva, who did not have a library education, perceived VGBIL as a casual and temporary place of employment, but soon realized that “this is my world, my abroad and my career.”

E.Yu. Genieva was a senior editor and researcher at Inostranka for 16 years, specializing in English and Irish prose of the 19th and 20th centuries. She has written prefaces and comments to books by Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, William Thackeray, Charlotte and Emily Brontë, Virginia Woolf, Susan Hill and other authors. At the end of the 80s, she prepared comments on the first complete translation into Russian of Ulysses. Although perestroika was underway, Joyce had not yet been officially rehabilitated in the Soviet Union, and the publication of his most famous novel was a bold step.

In the same 1989, when “Ulysses” was published in episodes in the magazine “Foreign Literature”, in the life of E.Yu. Genieva experienced a turning point: the staff of the Library of Foreign Literature, whose chairman was Ekaterina Yurievna, elected her director of the VGBIL. Faced with a choice whether to accept “Foreigner” or not, Genieva went to Archpriest Alexander Menu in Novaya Derevnya, near Moscow. Their paths had crossed again shortly before. “And it was a very intense communication - both the priest and his spiritual daughter, and just communication between two friends,” said Ekaterina Yuryevna. She announced to her confessor that she was inclined to refuse a leadership position that was incompatible with scientific work. Father Alexander “said: “You know, Katya, I won’t bless you for this.” And to the question: “When will I write?” - answered: “What are you, Leo Tolstoy? - but hastened to reassure: “Time will come to you...”.”

However, the Soviet Ministry of Culture entrusted the management of “Foreigner” to the prominent linguist and anthropologist V.V. Ivanov, and E.Yu. Genieva approved him as first deputy. Ivanov devoted most of his time to science, and the actual head of the library was Ekaterina Yuryevna. She provided Father Alexander Menu with a hall for preaching to the widest audience, and achieved the naming of VGBIL after its founder and first director, M.I. Rudomino, expelled from her post in 1973, founded the French Cultural Center together with the French Embassy in 1991, a landmark year for the country, and a year earlier organized an exhibition of the Russian émigré publishing house YMCA-Press (such actions could have serious consequences).

With the appointment of Ekaterina Yuryevna as director of “Inostranka” in 1993, the creation and development of foreign cultural centers became a priority area of activity for VGBIL. E.Yu. Genieva put into practice her vision of the library as a meeting place and intersection of different cultures, in which there are no ethnic, linguistic, or ideological barriers. She emphasized that the library, one of the oldest social institutions, acts as a space of dialogue, an open platform: Ekaterina Yuryevna liked to use these concepts when describing the concept of the functioning of the library she headed.

The Library of Foreign Literature is a single territory where the reader moves freely from the Dutch Educational Center to the Bulgarian Cultural Institute, from the House of Jewish Books to the Iranian Cultural Center, from the British Council to the Azerbaijan Cultural Center. In total, Inostranka has ten cultural centers. His long-term work E.Yu. In 2006, Genieva substantiated it theoretically in her dissertation “The Library as a Center for Intercultural Communication,” for which she was awarded the degree of Doctor of Pedagogical Sciences.

The director of VGBIL, which boasts literature in 145 languages and five million items, admitted: “The library card... is, to be honest, not very interesting to me. I am interested in what interests such a wonderful writer as Umberto Eco - philosophy, the magic of the library, how this library repeats life with all its possibilities.” The open area of VGBIL, in addition to islands of foreign cultures, was formed thanks to foreign language courses, propaganda of Russian culture abroad (in particular, the organization of translations of books by Russian writers), a program for the study and return of displaced cultural property, a Children's Hall, where young visitors feel like full users of the library , the Institute of Tolerance, which promotes better understanding between people of different nationalities and social views.

E.Yu. Genieva said: “Here children play on Joyce’s lap,” referring to the monument in the atrium of the VGBIL. The installation of sculptural images of outstanding minds of the past in the library’s courtyard is also the merit of Ekaterina Yuryevna. Heinrich Heine and Jaroslav Hasek, Simon Bolivar and Pope John Paul II, N.I. harmoniously coexist with each other. Novikov and Mahatma Gandhi, D.S. Likhachev and E.T. Gaidar...

Ekaterina Yuryevna was rightly called the ambassador of Russian culture. She has traveled all over the world, participating in conferences, round tables, and presentations. I came up with many of them myself. In April 2013, the author of these lines was lucky enough to visit E.Yu. Genieva in Spain: after very busy days in Madrid, we drove halfway across the country for about ten hours, during which Ekaterina Yuryevna discussed current affairs with her employees, then from early morning she held business meetings and flew to Moscow late in the evening. For her, such a rhythm was familiar and natural.

During that trip, I came into close contact with Ekaterina Yuryevna for the first time. I was impressed by her subtle mind, insight, ability to take a comprehensive approach to any issue, ability to listen and unobtrusively give wise advice. She was a rather reserved person, but at the same time, her sincerity and warmth were clearly visible. He spoke precisely and succinctly about E.Yu. The genius Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk expressed condolences on her death: “An amazing and warm-hearted woman with a truly Christian soul.”

Devotion to her calling - serving for the benefit of culture and people - was above all for Ekaterina Yuryevna. She even used forced trips to Israel for treatment for cancer to set up new projects. E.Yu. Genieva, the author of five monographs and more than two hundred articles, chairman and member of dozens of public associations, enjoyed international authority, had high awards from a number of states, but preferred not to talk about them.

She is characterized as a tough leader, but the general director of VGBIL communicated with her subordinates with emphatic tact, showed concern for them, and helped them find a professional path. “What does faith mean? - thought E.Yu. Genieva. “You feel that help and you understand that you not only have claims against those around you, you have a huge number of obligations to those around you.” No matter what country Ekaterina Yuryevna visited, she always returned with many gifts for colleagues, friends and acquaintances.

E.Yu. Genieva often visited Russian regions: she organized free deliveries of sets of books to local libraries, and brought with her writers, scientists, artists, performers, and directors. Lectures, creative conversations, master classes by prominent representatives of the cultural world, which attracted a huge number of guests and were covered in the press, set the further tone for intellectual life in the province.

Our last trip together took place in April of this year to Saratov. As part of the educational project “Big Reading,” we were invited to a small rural library in the Engels region, where Ekaterina Yuryevna spoke with the same passion, dedication and respect for the public as, say, in the elite literary club “Atheneum” in London.

It is impossible not to say that VGBIL is the first Russian library to have a department of religious literature. This happened in 1990 with the blessing of Archpriest Alexander Men. As already mentioned, E.Yu. Genieva has been a churchgoer since childhood. The Christian worldview was part of her personality. But, following her principles, she remained open to all religions. Ekaterina Yuryevna noted, not without pride: “In the religious department... books of the three world monotheistic religions and three main movements of Christianity stand on the shelves side by side.” The annual memorial evenings in honor of Father Alexander Men, dedicated to his birthday (January 22) and the anniversary of his death (September 9), serve as a kind of support for the interfaith and interreligious dialogue promoted by the VGBIL. Ekaterina Yuryevna considered preserving the memory of her spiritual mentor and friend as a personal duty.

E.Yu. Genieva worked closely with the All-Church Postgraduate and Doctoral Studies named after Saints Cyril and Methodius: she participated in conferences and gave lectures on intercultural communication and speech culture at advanced training courses. Students invariably recognized her as one of the best teachers: they were attracted not only by the deep content of the lectures, but also by the true intelligence and refined manner of speaking of Ekaterina Yuryevna. On June 23, 2015, she gave one of the last lectures in her life to the students of the regular OTSAD courses.

On July 9, 2015, after 15 months of fighting cancer in the fourth stage, E.Yu. Genius is gone. She died in the Holy Land. Ekaterina Yuryevna did not hide her diagnosis, setting an example of a courageous fight against a serious illness and completely relying on God’s Providence. The funeral service took place in the Church of the Unmercenary Saints Cosmas and Damian in Shubin on July 14, when the memory of Cosmas and Damian of Rome is honored. The funeral service was led by Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk. It is providential that exactly 24 years ago in this church, returned to the Moscow Patriarchate through the efforts of Ekaterina Yuryevna, the first Divine Liturgy in 70 years was celebrated.

E.Yu. Genieva was buried at the Vvedenskoye cemetery next to her mother, grandmother and grandfather. In this ancient Moscow cemetery, also called “German”, the “holy doctor” F.P., revered by Ekaterina Yuryevna, found rest. Haaz, Archpriest Alexy Mechev, to whom Elena Vasilyevna Genieva was close (after glorification as a saint, his relics were transferred to the Church of St. Nicholas in Klenniki), and Archpriest Nikolai Golubtsov, who baptized little Katya.

The Kingdom of Heaven and eternal memory of the servant of God Catherine.

Ekaterina Genieva, head of the All-Russian State Library for Foreign Literature since 1993, died at the age of 70. About this media reported her friends and colleagues. Genieva had cancer and was undergoing treatment in Israel.

Ekaterina Genieva has worked in this library since 1972. In 1989, she took the place of first deputy director of Inostranka, and in 1993, general director. Since 1997, she has headed the Russian Soros Foundation. Cultural centers of several foreign countries, including Japanese, American, and French, were opened in the Library of Foreign Literature. Here is Ekaterina Genieva’s last public speech, which took place on June 29, 2015 as part of the Open Library project in St. Petersburg:

Genieva gave one of her last interviews to Meduza; it was published on July 3. "I have a lot of bold plans. I have little time,– said Genieva.– When I was given a serious cancer diagnosis, I did not make it a secret either to my employees or to my supervisors at the Ministry of Culture. So we all played openly. And I can tell you that, if you don’t choose long words, then respect and understanding–this is exactly what I felt towards myself from everyone I worked with... I haven’t changed my lifestyle, I work the way I worked... It helped me gather my inner strength. And not lose your ability to work during these fourteen months. And endure both chemotherapy and operations, understanding how long it will last and what is happening to me".

A journalist talks about Ekaterina Genieva Alexander Arkhangelsky:

She said what she considered necessary, and did what she considered necessary, and in some strange way the state wave broke against her like a rock

- Ekaterina Genieva differed from people in power in that she acted and thought in terms of ideals, not interests. And this is how she always lived. Unlike those who like to speculate but cannot do anything, she was a man of action. She did not talk about how monstrous the life around her was, but tried and did everything so that at the point where she was, this life would not be so terrible. The library was surrounded by a wall, which neither ministries nor departments could completely destroy. The American Cultural Center operated in the library and continues to do so to this day, although I am almost sure that it will now be closed.

She never renounced the good work that Soros did here in the 90s, she was the president of the Soros Foundation and never hid it. I spoke with her in St. Petersburg 10 days before her death, it was her last public appearance, at the Mayakovsky Library, and there she talked about the foundation, about herself, about those cultural ties that cannot be sacrificed to politics. And she said what she considered necessary, and did what she considered necessary, and in some strange way, almost miraculously, the state wave broke against her like against a rock. There are fewer and fewer such people, and this is what they always say about the passing of great people, but it’s true. In this case, there will be absolutely no one to replace her. This is a huge loss for us. May she rest in heaven. It will be bad and difficult for us without her.

0:00 0:02:28 0:00

Pop-out playerEkaterina Genieva was a frequent guest of Radio Liberty; in one of the programs “From a Christian Point of View” she talked about her work at the Library of Foreign Literature and recalled Father Alexander Men, with whom she was friends.

No media source currently available

0:00 0:54:59 0:00

Pop-out playerIn one of the “Edges of Time” programs, released at the beginning of 2008, Ekaterina Genieva said that the closure of the British Council offices, which followed the tax claims of the Russian side, would primarily damage the Russian educational system.

No media source currently available

0:00 0:05:19 0:00

Pop-out playerAn economist, publicist, and former program director of the Open Russia Foundation remembers Ekaterina Genieva. Irina Yasin A:

– I have known Ekaterina Yuryevna since the late 90s and have always admired this woman. A true aristocrat of spirit, beauty, wisdom. Everything that was in it was wonderful! And we started working very closely when she was still the director of the Soros Foundation in Russia, the Open Society Institute, and we were doing “Open Russia” with Khodorkovsky. And I communicated with Ekaterina Yuryevna at work, then more closely, then she allowed me to call her Katya, so we became familiar and began visiting each other. In general, I was flattered that she called me her friend. If we talk about Katya’s services to the country, you still can’t say everything. In the 90s, many branches of science survived thanks to the Open Society Institute. She also carried out absolutely incredible projects that brought Russia closer to Europe and the world. She had many awards - a Japanese order, an English one, and an incredible number of others. And everything she received was deserved.

She traveled to small Russian towns more than any of those famous patriots who now love to talk about themselves.

This absolutely wonderful woman accumulated an incredible amount of wisdom, and besides, she was simply a very beautiful person. Straight back, beautiful hair, always dressed not richly, not chicly, but with taste and grace. We all learned a lot from her. Last year, when Katya was already seriously ill, she once said: “I want to die running.” I have never seen such a thirst for life. She planned for years ahead: we will do this this year, next year... we have this project, this project, these books, these libraries... She traveled not only to Europe, she traveled to small Russian cities more than any of those notorious patriots who now love to talk about themselves.

A man of great courage and beauty

And of course, in recent years, when Russia began to turn its back on the West at the behest of our leadership, it was hard for it to survive, simply because the same American Cultural Center, which had been working in the Library of Foreign Literature since Soviet times, in the late 80s x was organized, and I don’t know whether they will talk about it or not, but Katya was demanded to close it, and Ekaterina Yuryevna resisted as best she could, wrote, demanded that they, I won’t say who exactly, do it themselves so that they give her an order. She is, after all, a civil servant, a library director, and she would have fulfilled it, but she, of course, would not have closed such an important institution with her own hands. A man of great courage and beauty. Recently, when we met very often in Israel, she on her medical affairs, I on mine, we didn’t talk about illnesses at all. Never! It was taboo. Because illnesses are what prevent us from living. That's how she died, on the run, just as she wanted. Ekaterina Yuryevna was a spiritual basis for me, a very important person in my life,” said Irina Yasina.

Ekaterina Yuryevna Genieva was born into the family of actor Yuri Aronovich Rosenblit (1911-2002) and surgeon Elena Nikolaevna Genieva (1917-1982). The parents soon separated, the mother got a job in the medical unit of the ITL in Magadan, and E. Yu. Genieva spent her early childhood in the family of her mother’s parents. Grandmother, Elena Vasilyevna Genieva (née Kirsanova; 1891-1979), in 1921-1926, annually vacationed in Maximilian Voloshin’s “House of Poets” in Koktebel, corresponded with a number of figures in Russian literature; her correspondence from 1925-1933 with S.N. Durylin was published as a separate book (“I don’t write to anyone like I write to you”). Grandfather, hydrological engineer Nikolai Nikolaevich Geniev (1882-1953).

Ekaterina Yuryevna Genieva graduated from the Faculty of Philology of Moscow State University (1968), Candidate of Philological Sciences, and defended her doctoral dissertation in 2006. Specialist in English prose of the 19th-20th centuries. Author of articles and commentaries on the works of Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, Charlotte and Emily Brontë, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Susan Hill and other authors.

Since 1972 he has been working at the All-Union State Library of Foreign Literature. Since 1989, First Deputy Director, since 1993, General Director. Vice-President of the Russian Library Association, First Vice-President of the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions - IFLA (since 1997).

Since October 1997, Genieva has been President of the Russian Soros Foundation (Open Society Institute), Vice-President of the International Federation of Libraries (IFLA), Member of the Russian Federation Commission for UNESCO, President of the Russian Council for Culture and the Arts, President of the Moscow Branch of the English Speaking Union (ESU) ). Member of the editorial boards of the magazines “Foreign Literature” and “Znamya”, over the years she was a member of the editorial boards and boards of the magazines and newspapers “Children’s Literature”, “Library”, “Russian Thought”, etc.

"AND TIME WILL SEND YOU..."

Indeed, every person is a genius in their own way. And it is very valuable when such people are open to communication, ready to share experiences, ideas and, importantly, the ability to implement them. And despite the events taking place around such Personalities, a special world, a special space is always created. Their energy attracts, and life is filled with an incredible number of ideas, plans and projects. And it seems that it is impossible to be on time everywhere, but suddenly time appears and projects are implemented. You just need to stop sometimes... and look back, so as not to lose yourself and those who are nearby, or those who are already only in the heart...

Ekaterina Yuryevna, from childhood you were surrounded by books and thinking people who taught you to read. You were raised by a wonderful grandmother. You had a wonderful library. How did you manage to bring this love of books into your life and work, to combine it with active work and relaxation, if such a concept exists in your life?

- I am, of course, very lucky with my family. And over time, the memories that return to the pictures of childhood become more and more poignant - at the dacha, every morning, after breakfast, my grandmother and I sat on a wonderful carved sofa, she opened huge volumes of the Bible with illustrations by Gustave Doré and in good French (my grandmother spoke to me in -French) explained what was drawn in the book. After evening tea, she took an Italian newspaper, which published the very funny adventures of some Italian gentleman. Being near a book was as natural to me as breakfast, lunch or dinner. But I was even luckier. There were people around me who knew how to handle a book, who knew how to show its fascination and appeal, its aroma, its value - this is great happiness.

My grandmother truly was an absolutely amazing person. A person of the pre-revolutionary era, a Smolyanka, she, whether she wanted it or not, received the education that girls from noble families received in the institutes for noble maidens. After the revolution she never worked. This opportunity was provided to her by her husband, Professor Geniev. She translated, but rather for herself. By the end of her rather long life, my grandmother knew fourteen languages and spoke five or six European languages completely fluently. And this was also a natural habitat for me. At home we communicated only in French, and all the defects in my speech are due to the fact that as a child I did not learn to correctly pronounce difficult Russian sounds. I speak French as fluently as I speak Russian; my grandmother taught me English, but my grandfather and I spoke only German. Since childhood, such multilingualism has fostered a deep sense of tolerance and equally respectful attitude towards another language, another culture.

I was not a very healthy child, I was sick a lot, I lay in bed, and adults read to me. This is generally a wonderful thing that is leaving our lives - reading aloud to a child. So, in my opinion, all of Pushkin was read to me; Shakespeare, probably not all of it, but at least things that I could understand. When I entered Moscow State University, I believed that all people knew what the Bible said - after all, it was a fact of my everyday life. And I was shocked when I found out that people don’t know this story. One of the reasons why I entered not the Russian department, but the Western, Romano-Germanic one, was that I was convinced that Russian poetry, the poetry of the Silver Age, Voloshin, Tsvetaeva, Mandelstam, were known to everyone. A close friend of my grandmother, with whom she kept correspondence until the end of her life, was Maximilian Voloshin. I also thought that everyone knew him. I, of course, grew up in a privileged, literary family. And such figures as Mikhail Vasilyevich Nesterov or Sergei Nikolaevich Durylin were my own, “people at the table.” It’s unlikely that at the age of 6 or 8 I understood the significance of Nesterov’s work, although his paintings hung in our house. (Fortunately, some are still hanging.) But I remember very well the conversations they had with my grandmother. After all, Nesterov had very difficult years. His phrase that potatoes should be served on a silver plate (which, apparently, remained from better times) is etched in my memory forever. Therefore, when I lived with my daughter and her friends at the dacha, I served potatoes and pasta in the navy style not on a silver plate, of course (I simply didn’t have one), but with snack plates, plates for the first, for the second, etc. . used constantly. And then the children washed all the dishes in basins together. This is also part of the culture. Culture is not only if we read a book, but also how we perceive ourselves and feel in life.

I, of course, did not understand the significance of Sergei Nikolaevich Durylin, his works about Lermontov, his place in Russian culture. For me, it was just someone we went to visit. Now I am publishing a book - correspondence between my grandmother Elena Vasilyevna Genieva and Sergei Nikolaevich Durylin.

Usually there was silence in the house because grandfather was working. But I was allowed everything: to ride a tricycle around the professor’s apartment, to tinker with manuscripts on the table where graduate work lay. However, what attracted me most (since it was forbidden to touch) was a small suitcase that always stood ready near the office. I really wanted to make it into a doll's bedroom or something similar. Of course, I didn’t understand what it was for. It was a suitcase in case of a knock on the door. Fortunately, my grandfather had no use for it. But the Gulag did not bypass our family, like almost any family in Russia. My uncle Igor Konstantinovich Romanovich, a famous translator from English, died of starvation in a camp near Rybinsk. He died only for working with Western literature.

As you can see, there were quite a lot of factors that shaped my personality. I don’t want to say at all that everything was rosy. Firstly, this doesn’t happen, and secondly, my life could have turned out completely differently. My parents divorced before I was born, although they maintained a very good relationship. My mother, Elena Nikolaevna Genieva, was a very bright and enthusiastic person. During the war, the parents were called up as actors of Mosestrad (ignoring their main specialties - a doctor and a chemist). For my mother it was a tragedy, and she, being a beautiful and stubborn woman, reached Stalin’s reception room, where they explained to her: “We have many good doctors, but few good actors. So do what you were sent to do." Perhaps that's why they survived. After the war, not a single clinic hired my mother. I was probably ten months old when she, leaving everything behind, went to Magadan, where she became the head of the sanitary and medical service. Her stories about Magadan of those years, about Kaplan, who shot Lenin, about her affair with the main boss of the camp - I heard all these fascinating stories only at the age of 6, when I saw my mother for the first time.

In general, I could have grown up completely different. I was left to my own devices, I could go wherever I wanted. But it was much more interesting for me at home, especially since I could bring any guests, all my young people. The usual question that my grandmother or mother greeted me with was: “Why did you come so early?” For the same reason, I never had the desire to smoke. My mother smoked, my grandmother smoked, and I think they wouldn’t mind if I smoked too. If my fate had turned out differently, I would have become a kind of bohemian creature.

But whether it was the prayers of my grandmother, who was a very religious person, or something instilled in my childhood, I turned out to be a very exemplary schoolgirl. I graduated from school with a gold medal, easily entered Moscow State University, where I studied with great enthusiasm, and entered graduate school. The classic path of a young successful philologist. But in graduate school I started having difficulties. I was offered a topic that some smart teachers from the department discouraged me from. But the figure of Joyce was connected with my family (I.K. Romanovich translated him), and at that time I had not read “Ulysses” either in Russian or in English, and knew only the stories “Dubliners” well. And I didn’t understand why I shouldn’t do this. I received everything in full during the defense. By this point, it was obvious that I had to step over myself and explain that Joyce, Kafka, Proust are alien writers whose works do not help build Magnitogorsk. That is, repeat the words of Zhdanov spoken at the congress of Soviet writers. As a result, I received four black balls. This defense became a phenomenon at the faculty - for the first time they did not throw mud at a modernist, but tried to analyze him. And then I had something completely unprecedented - redefending my PhD thesis at the Higher Attestation Commission, with negative reviews, everything as it should be. Nevertheless, I received my PhD.

I tried to get a job in a variety of places, and I was satisfied with everyone, having knowledge of languages, a philological education and a Ph.D. But the questionnaire said that I was half Russian, half Jewish. At this point it turned out that there were no places. And Joyce was in the way. I got a job at this library because my colleagues worked here - V.A. Skorodenko, our famous Englishist, and the late V.S. Muravyov. They offered me the position of bibliographer in the literature and art department. At that time, the library was headed by L.A. Kosygina, daughter of Kosygin, who replaced M.I. Rudomino. Lyudmila Alekseevna is, of course, an ambiguous figure. However, thanks to her, the library received scientific status and thereby attracted the cream of the literary community, who could not travel abroad. I was at the reception, by the way, in this same office. At L.A. Kosygina had a trait that was completely inappropriate for her status and position - insane shyness. Therefore, despite the persuasion of the personnel officer, she hired me without looking at the application form. So in 1972 I ended up here. And I have been working for almost 40 years.

I was engaged in acquisition, then worked in the literature and art department, which prepares our wonderful publications. And then came the era of M.S. Gorbachev, who led the country to the idea of labor collectives. Fermentation has begun. Lyudmila Alekseevna was no longer there; another director was appointed, though not for long, who clearly did not understand this library. In the end, they decided to choose, and then Vyacheslav Vsevolodovich Ivanov won. An amazing philologist, an unpublished writer, was expelled from Moscow State University. And suddenly everyone needed him, all the doors opened. He was invited to give lectures at all universities, and he was an honorary professor at the Library of Congress. And, of course, I didn’t devote much time to VGBIL (which is completely understandable from a human perspective). But the very fact of his directorship was very important, it showed that figures like him, Billington, etc. could head libraries. I was his deputy, in fact the acting director. When V.V. Ivanov finally established himself in one of the American universities, I became the director of this library. But in fact, I have been running it since 1989. By the way, I never intended to do this.

- But still got busy? And quite successfully.

- Yes, this is also a separate story. Father Alexander Men had a huge influence on the formation of my personality and destiny. I knew him from the age of four - his mother was friends with my grandmother. And Alik spent a lot of time at our dacha. When I realized that I would not be involved in translations, books, editing, and at any time, I would become the head of the library, I decided to consult with a person whose opinion was important to me. Having explained to him why I was not going to become a director, I heard a phrase that he had never uttered before, either during a service or in confession: “You know, I probably won’t bless you.” I was shocked by this phrase. “But time, where will I find time?” He probably had two or three months to live. I think he knew this. He said: “You know, time will come to you.” And this work, you know, I don’t perceive it as work. It's like a kind of obedience in monasteries.

Tell us what the library's success story is? How did you manage to create such a “center of gravity” for different cultures in such a difficult period from a historical and economic point of view in the early 1990s?

- I have never been a bureaucrat, an official. This bothered me and, at the same time, helped me a lot. For example, I didn’t understand why there was a need for a special storage facility, which seems to have been abolished. And I eliminated him. They immediately pointed out to me the need for a government decision. Having called some commission, I heard - everything is at your discretion. Although in other libraries the special storage was canceled much later. Under M.S. Gorbachev began to change, and I thought how wonderful it would be to collaborate with Western publishing houses. And she invited the emigration publishing house YMKA-Press to Moscow, simply by calling them on the phone from home. My husband, who overheard this conversation, told me: “You know, in Soviet times they gave you ten years for simply having YMKA-Press books in your library. There are easier ways to go to jail. I can tell you if you don’t know.” One way or another, the exhibition took place. After which I received an offer from the French Foreign Ministry to open a French cultural center in Moscow. On the one hand, I understood that I was not a diplomat and should not do this. But on the other hand, if your partner invites you to dance, he is unlikely to push both legs at once. Being a stubborn but law-abiding person, I went to see Minister Nikolai Nikolaevich Gubenko. He just waved his hand: “Forget it. Some kind of French center. Nobody is going to open anything." I replied: “Nikolai Nikolaevich, I warned you. I will open the center." And she flew to Paris, which she had never been to. I never saw Paris, because I spent the whole time in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where we drew up the agreement. And at this time Shevardnadze resigned. I had a wonderful night’s sleep in the hotel, and in the morning I went to the Ministry, “keeping my face.” And when I felt the pen in my hands to sign the agreement, I, speaking in literary language, felt very good. What I said, what they said, what happened at the official dinner, where there were people from different ministries, the government, from our embassy - I don’t remember anything. I kept thinking: what will I do when I return? It was a financial deal and I really needed it. 1991, no acquisition, the library of foreign literature could not exist at all, because there were no foreign exchange allocations. There was little choice: either cry, which is what the whole country was doing, or hang a lock on the library door, or do something. And I chose the last option. The result is a huge influx of books, funds received through intercultural agreement. We could spend this money on acquisition and development of the library. Library Development is not just the development of a library, it is the development of the very idea of a library. This includes staffing, personnel, training, social benefits, and premises. I was able to implement all this. It was a breakthrough.

And then - the British Council, the American Center, the Japanese Center, the Dutch Center, the Council of Europe, the House of Jewish Books, the current BBC television and radio stand. In those years, all this saved the library. And, of course, it created wild difficulties for me. Because our inspectors could not believe that the library director, who uses the entire library budget, is not corrupt, he does not have property in the south of France. Of course, we were checked endlessly. There was a year when 17 commissions arrived in a row. As a result, I asked for help from one famous lawyer, who, sitting in the same office, said: “Now write a letter to Primakov. And write the following: “If you order me in writing to close all these centers, then I will close them to hell right away.” As you understand, no one ever responded to this letter. But I wrote it.

- Where did you get the idea of an intercultural multilingual center from?

- When I was in Paris, they showed me the Library of the Georges Pompidou Center - the glory of the French nation. The center of Paris, a historical place, and suddenly a terrible metal caterpillar crawls. Well... modern architecture. A third of the cultural budget is spent on this miracle. The center does not close at night; there are queues at the library. When I came out, I didn't care if it was a caterpillar or a frog, because it was functional. I saw how on the territory of the library there was a community of many countries, many cultures, and I thought: “I also want the Georges Pompidou Center in Russia.” And she began to model the concept of library development on our Russian soil specifically for the idea of such a center. First, representations of the most developed languages of the world. And then, of course, the East. That is, the idea of a library is the idea of mysticism, mystery and greatness of the Book, which in fact is a world-forming building material. This is what we created.

You have a very vibrant life, you meet many interesting people, and actively participate in public life. But is there something you are afraid of?

- I'm afraid of only one thing - betrayal. This is the most terrible sin.

As for our country, I really hope that there is no turning back. I want to hope, because I’m not 100% convinced. On the one hand, the modern generation could no longer live in the reality in which, say, I grew up. But, on the other hand, when I see the real result of the “Name of Russia” program, I become scared. Of course, when we talk about war, Stalin's role must be considered from different angles. But if Moscow is decorated with his portraits on May 9... It will be a betrayal of the path that we have already traveled. I am convinced, for example, that Yegor Gaidar, who was my close friend and, I believe, never recovered from that poisoning in Ireland, saved Russia from civil war with his reforms. Probably all this should have been done somehow differently. But history has no subjunctive mood. If everything starts to come back, it will be a betrayal. I don’t know how applicable the category of betrayal is to history. History is a capricious lady.

You have been in the library for forty years. You know and see this society from the inside. Constantly changing legislation, there is no unity of opinion either in the library or book publishing community... Wherever you step, there is no movement... So what does this situation look like from the inside?

- This is, of course, scary, but not very scary. Maybe stupid, ridiculous, difficult. Any reasonable person will try to circumvent this law. Seminars are already being held on this topic, experts are speaking. I understand that in Russia laws are written in order to break them. It cannot be said that these laws are created by people who do not have knowledge or experience. I'm not a librarian, I'm a philologist, doctor of sciences. I probably don't need to run a library either. Billington - what kind of librarian? Famous Slavist. But only a person who has absolutely no understanding of what libraries do can equate a book with a nail. My favorite example. It is more profitable to buy not one nail, but ten for a ruble. But if you want to hang Repin’s “Barge Haulers” on this nail, then it’s better to buy one so that Repin doesn’t fall from this nail. Because Repin, unlike a nail, is not a replicable product. The book, although widely circulated, is also not a nail-biter. This is impossible to explain.

- There will be re-elections of the President of the RBA in May. Why did you decide to propose your candidacy and what are your priorities?

- The main question, of course, is “why?” To be honest, this was not part of my life plans. I satisfied my library vanity a long time ago (even though I almost didn’t have it). For eight years I served on the governing bodies of IFLA. If it weren’t for my involvement in the Russian Soros Foundation, I, of course, would have taken the place of IFLA president. But it was impossible to combine everything - the library, the Soros Foundation and IFLA. Why did I put forward my candidacy? In all normal library associations the presidential term is three years, a maximum of four, and more often two and a half. After which the president leaves his post. And not because he is bad or good, he can be brilliant, and the next one will be worse. But the new president will definitely have another priority program. And the library world is better for it. Under V.N. Zaitsev, the Association acquired its scale. He can be an honorary chairman, he really did a lot, and I was always on his side. I put forward my candidacy, having library experience, an international reputation, in order to disrupt this active library sleep. If I am elected (if! Because we are used to tomorrow being the same as yesterday, or even better, like the day before), I will strive to ensure that every day is new. I will work for two and a half years or three, and even if the entire library community begs me to stay, I will not stay under any pretext. I want to show by my example how it should be different. So that new forces flow into the community.

What are my priorities? The main one is probably not so much legal as moral and social. I want to continue what I started as vice-president of IFLA - to make our provincial libraries even more famous in the world. People should participate more widely in international activities and share experiences. My priority as director of the Library of Foreign Literature, one of the central federal libraries, is the province. A system of motivation and encouragement is extremely important - in different ways. And it’s time for many of us to seriously think about our successors. But there are almost no young people, that’s what’s scary. Before it’s too late, we need to create the conditions for it to appear.

Interviewed by Elena Beilina

Source: www.unkniga.ru/.

Ekaterina Yurievna GENIEVA: articles

Ekaterina Yurievna GENIEVA (1946-2015)- philologist, librarian, cultural and public figure, UNESCO expert, general director of the All-Russian Library of Foreign Literature from 1993 to 2015, in total she worked in this library for 43 years: | | | | | .SHEPHERD AND INTERLOCER

The story of my relationship with Father Alexander is both simple and complex. I had the happiness - during the life of Father Alexander, I did not realize that this was happiness - to know him from the age of four. We can say that he grew up in our house, because my grandmother, Irina Vasilievna, was very friendly with Irina Semyonovna Men, Fr. Alexandra. Alik was part of my childhood life and interior, at least that’s how I perceived him, although he was a unique object of both everyday life and interior: the young man was always reading something and writing something. Much later, I realized what he was reading - we had a large, miraculously preserved noble library, which contained many religious books. And he wrote “The Son of Man” - the book of his whole life. Then our paths diverged. He left for Irkutsk, I studied at Moscow University, then he returned, served in some parishes, then, until the end of his life, he “settled” in Novaya Derevnya.

Much later, in the last three or four years of his life, our paths became closely linked again, and this happened completely naturally: it happens - people have not seen each other for a thousand years, and then they meet, just as they parted yesterday. And it was a very intense communication - both the priest and his spiritual daughter, and just communication between two friends.

For me, he was, first of all, an endlessly interesting interlocutor. Moreover, both as a parish priest, a spiritual shepherd, and as a person who, before your eyes, talked with God. This conversation was difficult not to notice, and especially on the holiday of Trinity - it was his holiday, scorched by the Holy Spirit. And at confession (and he confessed wonderfully, it was never a formal act, even at general confession, when the church is full of people) he was an interlocutor, and with the whole country he was an interlocutor - I caught the period when he just started speaking. (He spoke publicly for the first time in our Library of Foreign Literature, and his last performance also took place here. The circle is closed.) He was an interlocutor both for my little daughter, who grew up before his eyes, and for my friends... He concentrated on yourself a huge amount of energy. It was kept in his heart, in his soul, mind and extended to everyone: from a simple parishioner, an eighty-year-old grandmother, to Alexander Galich, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, the famous Timofeev-Resovsky, “Zubr”, whom he baptized, Yudina... And it turned out that this human body is so easy to kill. But it was impossible to kill his great soul, which served the Higher Power.

He really served other forces - and we participated, were, as best we could, witnesses to this service. The power of his love for God was so all-encompassing that it could grind through human jealousy, discontent, and the difficulties of the time in which he lived. He had a hard time with his very peculiar church leaders, because many of them were simply sent by the relevant authorities. Everything was. But this man, of course, was chosen and chosen by a Higher Power to live at this time in Russia. Like Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov. They are very similar in some ways. Andrei Dmitrievich pacified the passions of the crowd with his quiet, barely audible voice. Father Alexander, with his loud voice, the voice of a biblical prophet, forced the whole country to listen to himself. Those forces that killed him physically and destroyed the fact of his presence in the world (which, of course, was, is and will be an irreparable loss), provided him, without realizing it, a platform no longer on the scale of Russia, but on the scale of the whole world - his the voice is heard and wants to be heard by the whole world.

Alexandra I get translated a lot today. But some of his fellow church members blamed him for not being a philosopher, not a church historian, but just a popularizer. I think about. Alexander is, of course, a philosophical mind and a great religious thinker of the twentieth century. But also, of course, a popularizer. This is his achievement, and not a minus, because - thanks to his education, faith, and pastoral service - he found wonderful words about Christ as the Son of Man. He has never been to Israel. And I was just there. And there I thought: how did it happen that a man who had never been here managed to tell more about Israel than my own eyes saw? He knew all this, he lived in it. And “Son of Man” is translated into many languages, works are written and translated about Fr. Alexandra. For the West, somewhat jaded, tired and spiritually sluggish, the image of Fr. Alexandra Me and his word are a kind of bell that awakens a dormant, tired, materialistic consciousness.

O. Alexander had a huge reserve of effective kindness and sincerity, the ability to simply talk about complex things and the gift of not condescending, but respectful persuasion. I saw how refined Moscow and St. Petersburg intellectuals came to his Novoderevensk church (and you still have to get to it) - he was a fashionable priest even in the years of stagnation. Many of those who came for the first time said: “Why do I need this priest? What can he tell me, a doctor, an academician?..” Once I watched such a meeting take place... Father Alexander approached one of these doubters, extended his hand and said: “And I’ve been waiting for you for so long... And now you have arrived.” This man was baptized a month later.

He didn’t pretend to be anything and didn’t put any pressure on anyone. Naturally, there is always a temptation to ask the spiritual father the question: what to do? In such cases, he answered: “I don’t know what to do.” He couldn’t tell you how to deal with minor everyday problems, but he knew perfectly well what to do when you asked him an essential question. I am just an example of this. After all, in a social sense, I am his work. I never wanted to control anything in life. But perestroika came, which in its powerful stream carried me along with other representatives of the intelligentsia... I understood: let’s make some noise, get excited, do something, and then I’ll return to my books and translations again... But when I had to make a decision , I was smart enough to consult with Fr. Alexander. And I asked him a question about how I should deal with the library (in consultation, I meant that I wasn’t actually going to do it), he said: “You know, Katyusha, I won’t bless you for this.” I say: “Why should I do it? Why me and not someone else? He says: “Well, someone has to do this. This someone will be you.” I object: “But I simply won’t be able to do this, I won’t have time...”. And then he said easily: “You know, time will come to you. I promise you this." I shrugged. But now that he is gone, I remember our conversation very often. After all, he, never demanding anything from his interlocutor, set such a mood that if your ears and eyes were at least half-open, you understood that by entering into a dialogue with him, you were involuntarily entering into a conversation with another, Higher power. O. Alexander helped everyone establish their own agreement with God, a bilateral agreement (not only given to you, but also constantly required of you).

He was a very gentle and kind person. Sometimes it seemed to me: why does he suffer with some of his parishioners, complex people, and often, perhaps, vicious. I told him: “You understand what kind of person this is...” He looked at me naively and said: “You know, Katya, you’re probably right, but what can you do - I’m a priest...”. And he added: “I’m trying to imagine how small they were...” Here I fell silent... Although, of course, he saw everything, he also saw the betrayal around him, which may have destroyed him...

I don't know what happened on that path. But I pictured it thousands of times in my imagination and I see that I am absolutely convinced that he knew the person who killed him. This was also a meeting... After all, Fr. Alexander was not a stupidly naive person. He wouldn't stop if someone just stopped him. It had to be someone I knew. This was Judas on his way to the Garden of Gethsemane, on the path of his life, which humbly repeated the life of Christ... Meeting on that path - with a kiss, a handshake, handing over pieces of paper... That was probably how it was programmed.

I have never experienced anything worse than his death in my life. Ten years have passed, but I remember everything in detail. It’s hard for me to talk about this, but when he was no longer there (and I didn’t know this yet), a picture of hell was revealed to me (this happened to me twice). It was the ninth of September, on the train - I was going to the dacha. There were people sitting around, and the combination was somehow strange. One woman looked like a resident of Sergiev Posad, she was whispering something all the time, maybe reading a prayer. The second one looked at me very strangely, very unkindly. I tried to work, but nothing worked, so I began to pray. And the woman opposite, like a broken record, repeated: “We need to take away the most precious thing from such people.” Then I thought: what did I do to her, why is she looking at me so strangely? She and her neighbor got off in Pushkin, at the station closest to Novaya Derevnya. And then the woman who was sitting with her back to me turned around. And I saw the face of the devil. I was deathly scared. At that moment I still didn’t understand anything. Later, when I came to my senses, I realized: something had happened, but what? Then they told me that Fr. Alexander was killed.

Of course, people killed him, but they were guided by devilish forces...

Probably, half of what I was able to do over the years, I would never have done without his, in church language, heavenly intercession. Can I say that I consider him a saint? Well, who am I to say this? I just feel his constant presence, I feel the love of people for him and his for all of us. And for myself I consider it a great happiness that I was familiar with him, that Fr. Alexander visited my house and married me and my husband.

Ekaterina Genieva is an activist quite well known in liberal circles. Firstly, she is the director of the All-Russian State Library of Foreign Literature named after. M. I. Rudomino (VGBIL). Secondly, in 1995-2003. she headed the Open Society Institute (Soros Foundation). Thirdly, she is the director of the Institute of Tolerance. And finally, fourthly, she is a member of the political party “Civic Platform” founded by Prokhorov. In the election campaign, she was even a contender for the post of Minister of Culture in Prokhorov’s possible government.

Not long ago we witnessed disgusting hypocrisy on the part of this lady.

She was invited to the program of the Public Television of Russia (OTR), where the topic was discussed - why, supposedly, Russia has ceased to be the most reading country in the world.

During her speech, Ekaterina Genieva expressed her thoughts on this issue. And it all boiled down to the fact that, they say, in our country there is “no political will” that would put book publishing and book distribution at the proper level. The lady complained that we put commerce before culture and that instead of creating bookstores, they prefer to trade in something more profitable.

What a twist!

This means that Genieva decided to shed crocodile tears that our culture is rotten! This is after she herself helped spread rot on this very culture for so many years!

Wasn’t Genieva wholeheartedly on the side of the bourgeois counter-revolution, the so-called “perestroika”?

Didn’t Genieva denigrate and help destroy Soviet socialism and all the achievements of the Soviet system - including the Soviet government’s concern for culture, for culture to be accessible to the broad masses, so that ever wider sections of the working people become involved in culture?

Didn’t Genieva do everything possible to ensure that capitalism was restored in our country - that system in which everything is built on money, on the pursuit of profit at any cost, and in which commerce will always come first, because it forms the basis of the bourgeois building? And everything else, including Genius’s kind culture, comes later, it’s only to this extent.

Didn’t Genieva defend and glorify the system in which a handful of robbers live at the expense of the robbed majority and can afford any whim? And the majority, the working class, the working people, are disadvantaged, deprived of essential material and spiritual benefits, including the opportunity to become involved in culture?

Wasn’t Genieva wholeheartedly in favor of “market relations” - that is, for such relations when everything is a commodity, everything is bought and sold - including culture?

And if culture is sold, this means that it is available only to the rich, and the majority of society is deprived of the opportunity to join it. In this case, the cultural level of the majority of society falls.

We now see all this with our own eyes - the decline in the cultural level of the majority of society, separated from genuine culture, and the emergence of a disgusting, corrupt, snobbish and contemptuous “elite culture” for the majority of the people.

And the reason for all this is the restoration of capitalism. Bourgeois counter-revolution under the name of “perestroika”, in which Genieva took a prominent part. She helped the bourgeois class a lot, provided a valuable service to the perestroika leaders who sought to destroy Soviet power in order to freely rob the people.

Let us list her “merits” in this direction (for which we, the working class, are especially “grateful” to her, and hope to get even in the future, after we destroy the bourgeois dictatorship and establish our workers’ power).

Firstly, Genieva turned the Library of Foreign Literature, which she headed - one of the best cultural institutions in the country - into a means of disintegrating society, denigrating Soviet power and promoting liberalism. Thus, in the garden (“atrium”) of the library there are monuments to three dozen people, among them a significant number of those who participated in the destruction of the USSR and the socialist camp (monuments to Alexander Menu, Dmitry Likhachev, John Paul II, and, most recently, Yegor Gaidar).

Secondly, the library publishing house has published many books on the topic of “the horrors of the totalitarian Soviet past.” Genieva did and is doing everything possible to slander the Soviet system, to slander socialism.

Since 2003, a joint project of the VGBIL and the Soros Foundation has been operating - the Institute of Tolerance. We think there is no need to explain in what direction this institution operates. As we have already said, Genieva is again the director of this institute.

But this is not enough. Genieva not only ideologically contributed to the restoration of capitalism and helped grabbers and robbers come to power. She herself acted in the spirit of these robbers - for a number of years, while serving as director of the library, she cynically enriched herself by theft of library funds and fraud with state property.

Here is some information about its past “economic” activities, which in 2011-2012. Anti-corruption authorities became interested.

In 2012, during an audit, numerous frauds with printed materials totaling about 5 million rubles were revealed.

In addition, an audit was carried out of the use of budgetary allocations in the amount of 20 million rubles, allocated by the reserve fund of the Government of the Russian Federation to finance the costs of creating digital copies of the book collections of the Esterhazy princes (the originals exported during the Great Patriotic War have now been returned to Austria).

As part of this “project,” payments to only five “ordinary” library employees amounted to about 8 million (!!!) rubles.

Genieva herself approved bonuses for herself and her subordinates for 2011, amounting to from 400 thousand to 1 million rubles, while the organization’s accountant, who has a “profile” diploma from a mining institute as a specialist “systems engineer” (!), received more than 3 million in a year rub.

It became known that the library does not maintain a procurement register, there are no waybills for the use of cars, there are no documents for performing contract work, contracts were concluded with individual library employees for the performance of work (services) that were part of their job responsibilities, work on building restoration...

However, all allocated funds were spent.

And this is not counting, to call a spade a spade, “kickbacks” from foreign cultural centers that do not pay taxes to our long-suffering state budget, having been located in the library for many, many years, starting from the “cheerful democratic” nineties.

In 2011 alone, the amount of unpaid (or hidden by Genieva in her wide, as it turns out, pocket) taxes ranges from 10 to 12 million rubles.

These sums, dear friends, were disbursed by the director of the library in only a year and a half, and Genieva has been leading the state institution for almost 22 years.

Can you imagine how much she has “mastered” during all this time?

The most disgusting thing in the current situation is the following.

The constant inspections cursed by Genieva nevertheless revealed a simply indecent scale of violations, multimillion-dollar theft, waste of budgetary and extrabudgetary funds, as well as an almost complete lack of control and connivance on her part. What do they usually do in such a case with an inept, and even stealing, boss? Of course, they do, not to mention the criminal legal consequences of such activities. It’s not for nothing that there is a saying about a fish rotting from the head.

But look at this zealous liberal!

To put things in order, and in fact create the appearance of order and well-being, with one stroke of the pen she dismisses a third of the library’s employees, completely ordinary workers who are far from the economic activities of the library and from herself, thereby killing two birds with one stone: to report on the punishment of the guilty and raise the salaries of those around you.

Having entered into a kind of rage of dismissing undesirables, the director of the library is trying by all means to get rid of the last remaining honest people in the leadership of VGBIL, who do not want to put up with the arbitrariness of corruption and are capable of taking the library into their own hands.

At the same time, it hides individual employees from all inspections.

And why?

Precisely because they know too much about the numerous frauds in the accounting department and the scale of corruption in the library.

Genieva’s motivation in this case is clear: who would so easily part with a gold mine, a kind of Klondike of Russian culture?

Fame, constant business trips, recognition on the international stage, generously sprinkled with sawn millions... Is it bad?

And for some reason, the raised funds demonstratively displayed by Ekaterina Yuryevna are in British and American banks...

Where do you think the director of the library got the money for two apartments in an elite building on the most prestigious site of the Garden Ring with a total area of 300 square meters in the hungry nineties? m?

Where do you think the director of the library got the money for two apartments in an elite building on the most prestigious site of the Garden Ring with a total area of 300 square meters in the hungry nineties? m?

According to realtors, the current cost of the Genieva mansion at 28/35 Novinsky Boulevard is about 100 million rubles!

And on a site in the near Moscow region in the Yaroslavl direction, 2 (!) mansions were built at once.

And this does not take into account the funds invested in real estate in Western Europe.

There is no need to mention a personal driver and maids in this case.

In short, the liberal lady did a good job! Not only did she help robbers come to power in the nineties, but she herself shamelessly acted in the same predatory spirit, stealing just like that.

So let this bourgeois bastard not deceive us with his hypocritical regret about the reluctance of young people to read and about the rottenness of our culture.

She and others like her have done especially much to bring back the criminal capitalist system and subjugate the working people to the rule of capital, under which we are deprived of culture, education, science, art, robbed, without rights, doomed to poverty and vegetation.

To people like this creature, a hypocrite and a thief, we should be especially grateful for this. And God willing, the time will come - we will thank you.

Red Agitator

55.614343 37.473446

On July 9, in one of the Israeli clinics, Ekaterina Genieva, the legendary head of the All-Russian State Library of Foreign Literature named after. M. I. Rudomino. Now it is still difficult to give a full assessment of the role that Ekaterina Yuryevna played in the cultural and social life of the country. She was not only the recognized keeper of the huge array of books that she inherited - that very “Babylonian library” glorified by Jorge Luis Borges - but also a translator, literary critic, publisher and public figure, biographically and creatively inextricably linked with the renewed Russia (as best she could, she until the very end prevented a return to the pre-perestroika era). Communicating with her, few doubted that “the world was made for books.” Indirectly or directly, she participated in many cultural projects. In recent years, another one has been added to them: Ekaterina Yurievna became an active member of the Academic Council of the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center and brought her unique “genius” scale and enthusiasm to its work. Ekaterina Yuryevna Genieva is remembered by the Chief Rabbi of Russia Berl Lazar, publisher, head of the Gesharim/Bridges of Culture association Mikhail Grinberg, historian, teacher at the Academy. Maimonides and the Department of Judaic Studies at ISAA Moscow State University, senior researcher at the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center Ilya Barkussky, translator from English, literary critic, editor-in-chief of the journal “Foreign Literature” Alexander Livergant, historian, director of the Center for Jewish Studies and Jewish Civilization at ISAA Moscow State University, chairman of the Academic Council of the Jewish museum and tolerance center Arkady Kovelman.

“our task is to help the projects of genius come true”

R. Berl Lazar I have known Ekaterina Yuryevna for a long time, probably twenty years. Ekaterina Yuryevna has always been our like-minded person. Her activities were largely aimed at promoting tolerance and developing interethnic dialogue in Russia and around the world; she headed many socially significant cultural projects. FEOR sets itself the same goals. In 2003, she headed the “Institute of Tolerance”; in 2005, under her leadership, the “Holocaust Encyclopedia” project was created, for which she was awarded the FEOR “Person of the Year” award (today the award is called “Fiddler on the Roof”) in the “Public” category activity". In 2012, the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center was opened, and we invited Ekaterina Yuryevna to join its Academic Council.

As for the situation that arose when the books of the Schneerson dynasty were transferred to the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center after the decision of the American judge Lambert. In this truly difficult situation, Ekaterina Genieva acted from the position of curator of cultural projects. Her opinion was clear: the Schneerson Library needed to be popularized, made open and accessible to the religious and scientific community, and all parts of the collection collected in one place. She advocated serious expert work to identify the contents (composition and number of volumes) of the Schneerson library and gave examples of policy decisions on the transfer of collections and libraries from state storage in similar situations to third parties and organizations. In general, she advocated negotiations between all interested parties (the Jewish community of Russia, representatives of the American Chabad organization from the United States, experts, museum workers and the Russian government) and the search for a compromise solution to the issue of transferring the library for study and use by the Jewish community.

“Institute of Tolerance” is a project of the All-Russian State Library of Foreign Literature. Genieva was its ideologist, initiator, and main driving force.

This is a huge loss for the entire Jewish Museum team. The memory of Ekaterina Yuryevna will forever remain in our hearts. We have an idea to hold an evening in her memory with the participation of colleagues, close people and everyone who was not indifferent to her work. Ekaterina Yuryevna had many projects to maintain and develop Jewish culture and tradition in Russia, unfortunately, not all of them were implemented, and our task is to help them come true, this would be the best manifestation of honoring an outstanding person.

“KATIN’S IDEAS CONTINUALLY TURNED INTO REALITY”

Mikhail Grinberg In the summer of 1989, when I was already a citizen of Israel, I had to accompany groups of Hasidic pilgrims to Ukraine, and during a two-week break I managed to escape to Moscow. At that time, I was overwhelmed by the idea of Jewish publishing: the scarcity or almost complete absence of books on Jewish history and tradition gave me a strong desire to restore justice. They gave me the address of a Lithuanian businessman associated with the printing business (there was much more freedom in Lithuania at that time), I called him and arranged a meeting. I talked, and soon the first Jewish prayer book in many years and the philosophical “Tanya” were published in Vilnius. And already in Moscow, he met with two future founders of the largest publishing house “Terra” in the 1990s and helped them register as a publishing branch of a sewing cooperative. Thus, their official activity began with two Jewish books - about a woman in the Jewish tradition and the memoirs of Professor Branover. At the same time, in Moscow, they told me about the active work of the Library of Foreign Literature to introduce new ideas into the mass consciousness. They organized various round tables, book exhibitions and photo vernissages, including on religious topics, with the assistance of Christian organizations and the YMCA-Press.

In Soviet times, among those who did not accept the official ideology, there were many different informal groups, and their participants provided mutual support to each other whenever possible. It was already the fifth year of perestroika, but the recommendations worked. Genieva was then the deputy director of Inostranka, and the wife of my institute mentor and friend Tatyana Borisovna Menskaya studied with her at the philological department of Moscow State University. The director of the library at that time was Koma (Vyacheslav Vsevolodovich) Ivanov, who worked together with Boris Andreevich Uspensky, with whom I was familiar. We met Ivanov, and I suggested him a theme for the exhibition: “Jewish religious book in Russian.” The times were difficult, diplomatic relations with Israel had not yet been established, and the word “Zionism” had a derogatory connotation. Tens of thousands of Jews of the USSR hastily packed their suitcases under the propaganda squeal of the Memory society, and my “acquaintance” Ivan Snychev (soon appointed Metropolitan to the St. Petersburg see) carried out ideological work to expose “Jewry as a tool of the Antichrist.” I asked Academician Ivanov an immodest question: “Are we going to be afraid?” - he answered: “No,” and Katya Genieva joyfully took the matter of preparing the exhibition into her own hands. Having persuaded the “groom,” I went to Israel and invited the director of the Shamir publishing house to join the project as a partner of the Library of Foreign Literature. At the same time, the presence of the Gesharim/Bridges of Culture association, which formally did not yet exist, was also indicated among the exhibition participants. Books for the exhibition were provided by the Shamir publishing house together with the Joint, which was then beginning to restore its presence in the USSR.

Everything went great: in January 1990, the exhibition was opened with a large crowd of people, and then it went through the cities and villages of Russia, Belarus and Latvia.

Together with the Soros Foundation, we published only one book, but in 1998 the library’s publishing department approached us as the first publishers of Bruno Schulz’s works in Russian with a proposal to support the publication of the book “Bruno Schulz. Bibliographic index". Katya created or contributed to the creation of numerous structures, one way or another integrated into Russian culture. And many people, employees of Inostranka herself and associated organizations, went on an independent voyage, receiving a charge of vigor and experience from her. For example, the director of the main children's library of Russia Masha Vedenyapina, the director of the Center for Russian Abroad Viktor Moskvin and many others. Our association, “Bridges of Culture,” has held events in Inostranka many times: round tables, presentations of new books. We talked at fairs and exhibitions. And five years ago we held a gala meeting in honor of the 20th anniversary of that very first exhibition of Jewish books.

Recently, Katya often came to Israel, and the Russian ambassador encouraged us to cooperate. We met several times, discussed future joint publications by Lermontov, Akhmatova, Pasternak, and other authors in Russian and Hebrew. They were supposed to be carried out jointly with the Institute of Translation created by Genieva.

She was sick and came to the country for treatment. The treatment was very difficult, but she worked and made plans for the future as if she had no doubt that together we would complete our work and move on to the next plans, which Katya almost invariably turned into reality. Of course, she was a figure of Russian culture, but she also perceived it as an important component of the world and therefore did her best to make this recognized in other countries: she proudly told how she was able to hold events dedicated to Lermontov in Scotland last year, overcoming the British arrogance and the current pushing away of the West from Russia. And she had a special, I would even say, sentimental attitude towards Jewish culture, which was probably associated both with her origin and with Christian attitudes in line with Menev’s interpretation of Christianity. From my experience of communicating with her: everything that had to do with bringing Jewish culture and tradition to Russia was perceived by her as the most important part of her work.

“THIS LOSS APPEARS CATASTROPHIC”